- History

- Plant description

- Growing methods

- Soil

- Irrigation

- Varieties

- Yields

- Seeding and planting

- Why flooding rice fields?

- Growth stages

- Rice maturation and harvesting

1.1 The importance of rice cultivation

Rice in Asia and the global food supply

Sources: IPI, 2006 and FAO, 2008

Rice is the main staple food in Asia, where about 90% of the world's rice is produced and consumed. China is the world's biggest producer, growing one-third of Asia's total on 29 million ha (Table 1.1). India produces nearly a quarter on 43 million ha. Other top rice-producing countries in Asia are mentioned in table 1.1 too. Average yields in these countries range from 2.6 to 6.5 t/ha*.

Table 1.1: Average annual rice production, area harvested, and yield in most important

| Country or region | Production (million tons) * | Area harvested (Million ha) | Yield (t/ha) |

| China | 188.5 | 28.7 | 6.5 |

| India | 142.5 | 42.8 | 3.3 |

| Indonesia | 58.3 | 11.7 | 5.0 |

| Bangladesh | 42.5 | 10.9 | 3.9 |

| Vietnam | 36.0 | 7.5 | 4.8 |

| Thailand | 30.5 | 9.9 | 2.6 |

| Myanmar | 32.0 | 8.9 | 3.6 |

| Philippines | 17.5 | 4.6 | 3.8 |

| Japan | 10.9 | 1.7 | 6.4 |

| Other Asian countries | 35.8 | 10.9 | 3.3 |

| Asia | 594.5 | 137.6 | 4.3 |

| Brazil | 12.1 | ||

| World | 597.8 | 155.0 | 3.9 |

* All tonnage terms in this publication are metric, unless otherwise indicated.

Worldwide, around 79 million ha of rice is grown under irrigated conditions. While this is only half of the total rice area, it accounts for about 75% of the world's annual rice production. In Asia, nearly 60% of the 138 million hectares devoted to rice production annually is irrigated, where rice is often grown in monoculture with two to three crops a year depending upon water availability. Other rice ecosystems include the rainfed lowland (35% of total rice area), characterized by a lack of water control, with floods and drought being potential problems, and the upland and deepwater ecosystems (5% of total rice area), where yields are low and extremely variable.

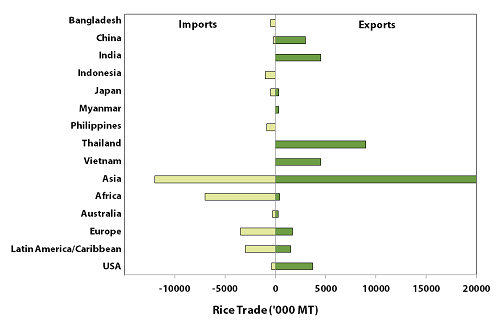

Thailand is the world's major rice trader, exporting an average of 8 million tons of rice annually (Figure 1.1). Vietnam and India export a total of 7 million tons. A positive trade balance for rice has been maintained by Asia, Australia and the United States. Latin America, Africa, and Europe, are net importers of rice.

Figure 1.1: Global rice trade - average of data for 2000 to 2004 (FAO 2006)

The demand for rice is expected to grow for many years to come largely because of population growth, particularly in Asia, where population is expected to increase 35% by 2025 (United Nations, 1999). An increase in total rice production may come from an increase in the area planted, increased yields, and increased cropping intensity. However, the scope for expansion of rice-growing areas is limited because of loss of agricultural land to urbanization, land conversion, and industrialization. Therefore, future increase in rice supply must come from increased yields and intensified cropping, particularly in the irrigated rice ecosystem.

There is substantial scope to increase current rice yields as farmers in Asia, on average, achieve only about 60% of the yield potentially achievable with existing varieties and climatic conditions. The main limitation to achieving higher yields and associated higher profitability for rice farmers per unit of arable land is often the ineffective use of inputs (particularly nutrients, seed, and pesticide) in an environmentally sustainable fashion. If the demand for food is to be met, rice production will need to become more efficient in the use of increasingly scarce natural resources. Better crop, nutrient, pest, and water management practices, along with the use of germplasm with a higher yield potential, are required in order for rice production to be profitable for producers and to supply sufficient affordable staple food for consumers.

1.2 History

Many historians believe that rice was grown as far back as 5000 B.C.

Archaeologists excavating in India discovered rice, which they were convinced, could be dated to 4530 B.C. However, the first recorded mention originates from China in 2800 B.C. Around 500 B.C. cultivation spread to parts of India, Iran, Iraq, Egypt and eventually to Japan. Although China, India or Thailand cannot be identified as the home of the rice plant (indeed it may have been native to all), it is relatively clear that rice was introduced to Europe and the Americas, by travelers who took with them the seeds of the crops that grew in their homes and in foreign lands.

In the West, parts of America and certain regions of Europe, such as Italy and Spain, are able to provide the correct climate thereby giving rise to a thriving rice industry. The first cultivation in the U.S., along coastal regions from S. Carolina to Texas, started in 1685. Some historians believe that rice travelled to America in 1694, in a British ship bound for Madagascar.

1.3 Plant description

Rice plant is an annual warm-season grass (monocot plant) with round culms, flat leaves and terminal panicles.

Rice is normally grown as an annual plant, although in tropical areas it can survive as a perennial and can produce a ratoon crop up to 20 years. The rice plant can grow to 1–1.8 m tall, occasionally more, depending on the variety and soil fertility. The grass has long, slender leaves 50–100 cm long and 2–2.5 cm broad. The small wind-pollinated flowers are produced in a branched arching to pendulous inflorescence 30–50 cm long. The edible seed is a grain (caryopsis) 5–12 mm long and 2–3 mm thick.

The grain

The single seed is fused with the wall, which is the pericarp of the ripened ovary forming the grain. Each rice panicle (which is a determinate inflorescence on the terminal shoot), when ripened, contains on average 80-120 grains, depending on varietal characteristics, environmental conditions and the level of crop management. The floral organs are modified shoots consisting of a panicle, on which are arranged a number of spikelets. Each spikelet bears a floret which, when fertilized, develops into a grain.

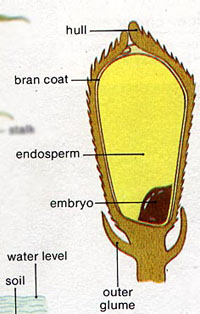

Rice grain structure

A kernel of rice consists of a hull and a bran coat, both of which are removed on polishing "white" rice. In general, each rice kernel is composed of the following layers:

- Rice shell, hull or husk: encloses the bran coat, the embryo and the endosperm.

- Bran Coat (layer): a very thin layer of differentiated tissues. The layer contains fiber, vitamin B, protein and fat. The most nutritious part of rice resides in this layer.

- Embryo: The innermost part of a rice grain consists mainly of starch called amylase and amylo pectin. The mixture of these two starches determines the cooking texture of rice.

A crop producing on average 300 panicles per m2 and 100 spikelets per panicle, with an average spikelet sterility of 15 % at maturity and a 1000-grain weight of 20 g will have an expected yield of 5.1 t/ha.

Figure 1.3: Cross section of a rice seed

Rice roots (and many other wetland plants) have special anatomy: aerenchyma vessels to get oxygen down to cells in root tissue (because wetlands have little dissolved O2 in the water.

Figure 1.4: Rice stem cross sectionmagnified 400 times

Figure 1.5: Aerenchyma vessels

Genotypes of rice

- Oryza sativa var. indica: mostly long grain types, grown in the southeast US.

- Oryza sativa var. japonica: mostly short and medium grain types, grown in Asia and California, preferred types in the Asian markets.

- Red rice. Oryza sativa: a weed.

1.4 Growing methods of rice

Figure 1.6: Upland

Figure 1.7: Lowland

1.5 Soil

Soil type: A rice paddy needs to hold water well. Ideally, soil needs to include about 50% clay content. Also, soil underlain with an impervious hardpan or clay-pan helps to hold water.

1.6 Irrigation

Rice can grow in either a wet (paddy) or a dry (field) setting. (Rice fields are also called paddy fields or rice paddies).

About 75% of the global rice production comes from irrigated rice systems because most rice varieties express their full yield potential when water supply is adequate.

In cooler areas, during late spring, water serves also as a heat-holding medium and creates a much milder environment for rice growing.

A pond could hold irrigation water to use in the summer, when demand for water is the greatest.

The bulk of the rice in Asia is grown during the wet season starting in June-July, and dependence on rainfall is the most limiting production constraint for rain-fed culture. Rice areas in South and Southeast Asia may, in general, be classified into irrigated, rain-fed upland, rain-fed shallow water lowland and rain-fed deep water lowland areas.

The productivity of well-managed, irrigated rice is highest, being in the range of 5-8 t/ha during the wet season and 7-10 t/ha during the dry season if very well managed, but the average is often only in the range of 3-5 t/ha. The productivity of rain-fed upland and deep water lowland rice, however, continues to be low and is static around 1.0 t/ha.

1.7 Varieties

There are more than 40,000 varieties of cultivated rice (Oryza sativa L.), but the exact figure is uncertain. Over 90,000 samples of cultivated and wild rice species are stored at the International Rice Gene Bank and these are used by researchers all over the world.

There are four main types of rice: Indica, Japonica, aromatic, and glutinous. Rice seeds vary in shape, size, width, length, color and aroma. There are many different varieties of rice: drought-resistant, pest-resistant, flood-resistant, saline-resistant, tall, short, aromatic, sticky, with red, violet, brown, or black; long and slender; or short and round grains.

Extensive studies of the varieties have demonstrated that they were independently derived from the wild rice species Oryza rufipogon. The domesticated varieties show much less variation (polymorphism) than the wild species.

Rice cultivars (Oryza sativa L.) are divisible into the Indica and Japonica types, or subspecies indica and japonica, which differ in various morphophysiological traits. These two main varieties of domesticated rice (Oryza sativa), one variety, O. sativa indica can be found in India and Southeast Asia while the other, O. sativa japonica, is mostly cultivated in Southern China.

In general, the rice family can be broken down into three main categories:

- Long Grain: Approx. 6-8 mm long, about 3-4 times longer than thick. The endosperm is hard and vitreous. The best long grain varieties come from Thailand, Southern US, India, Pakistan, Indonesia and Vietnam.

- Medium Grain: Approx. 5-6 mm long, but thicker than long grain rice. The endosperm is soft and chalky. It releases about 15% starch into water during cooking. Medium grain rice is mainly grown in China, Egypt and Italy.

- Short Grain or Round Grain: Approx. 4-5 mm long, only 1.5-2 times longer than thick. The endosperm is soft and chalky. This variety is grown in subtropical areas like California, Egypt, Italy, Japan, Korea, Spain and Portugal.

1.8 Yields

Yield gap is literally defined as the difference between yield potential of rice and yields that are actually obtained by farmers.

Yield potential of traditional Indica varieties is about 5 t/ha, while yield potential of crossbreedingJaponica varieties x with high-yielding Indica varieties,is about 10 t/ha Yield potential of high-yielding Japonica varieties is about 15 t/ha while the yield potential of hybrid varieties is about 18 t/ha.

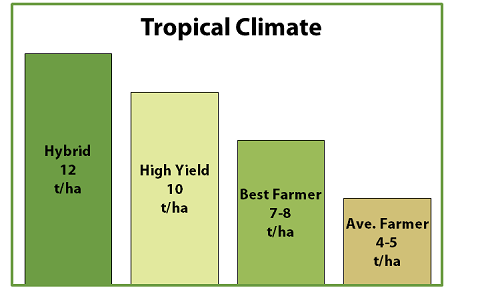

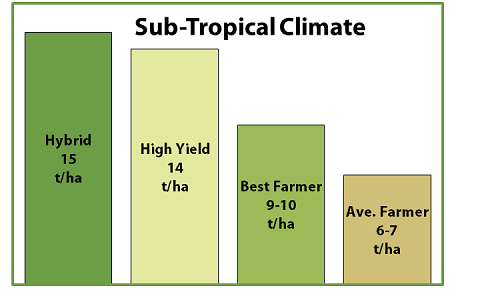

The yield gap in irrigated rice production is graphically presented in Figure 1.8. It shows the gap of about 4-6 t/ha in both Tropical (e.g. Philippines) and sub-tropical climate (e.g. Japan).

Figure 1.8: Average yields in two different climate conditions under different growing regimes

After the development of IR8 and other high-yielding rice varieties, considerable efforts have been devoted to the development and dissemination of improved technologies for cultivationtechnologies, in order to fully benefit from the yield potential of the developed varieties.

The Green Revolution

New ‘Super Rice’ was released in 2000, featuring a 35% yield increase. Genetic material from corn was inserted into rice plant. This raised the efficiency of photosynthesis. The new varieties consist of fewer but stronger tillers carrying more grains per inflorescence. Half of the IR8 plant’s weight is grain and half is straw, whereas the new Super Rice plant is 60% grain and 40% straw.

Figure 1.9 shows that from 1970 to 1985, rice yields in Australia stagnated at around 6 t/ha.

After the dissemination of the Rice-Check system in 1986, the Australian national yield increased rapidly and steadily from about 6 t/ha in 1987 to above 9 t/ha in 2000.

It was reported that application of the Rice-Check system also increased the nitrogen fertilizer usage efficiency.

The rice production systems in Australia and their conditions, however, are very different to those in developing countries.

Rice yields vary enormously across ecosystems and countries. Yields of 4–6 t/ha are common in irrigated settings, as are yields of 2–3 t/ha in rain-fed ecologies. Where rainfall is unreliable and drainage is poor, farmers still grow traditional varieties and use fertilizers in suboptimal amounts because of the uncertainty of obtaining adequate returns from investment in inputs.

Recent analyses suggest that growth rates of yields are increasingly differing between and within countries. In three out of four major rice-producing countries, the growth in average yields over the past 20 years is higher than the standard deviation of yield growth by provinces in the respective countries (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2: Yield differences of rice within countries in the 1980s and 1990s.

Average annual growth rates (%) in national average cereal yield and sub-national variation

| Country | Average growth per annum (%) | Standard deviation (sub-national variation) |

| Bangladesh | 1.8 | 5.1 |

| Brazil | 4.6 | 2.3 |

| China | 2.1 | 1.7 |

| India | 2.3 | 2.4 |

Source: Schreinemachers (2004)

Table 1.3: Average yields of rice varieties *

| Average grain yield | ||

| bushels/acre | t/ha | |

| Bengal | 170 | 8.5 |

| Cocodrie | 165 | 8.3 |

| Cypress | 150 | 7.5 |

| Drew | 160 | 8 |

| Jefferson | 145 | 7.3 |

| Kaybonnet | 150 | 7.5 |

| LaGrue | 175 | 8.8 |

| Madison3 | 160 | 8 |

| Priscilla3 | 155 | 7.8 |

| Wells | 170 | 8.5 |

*Arkansas rice performance trials of a 3-year study

1.9 Seeding and planting rice

Several seeding and planting methods are practiced:

- Dry seeding with drill.

- Dry seeding by broadcast or air. Most of the rice, in large fields, is sown by aircraft. Experienced agricultural pilots use satellite guidance technology to broadcast seed accurately over the fields.

- Water seeding with pre-germinated seed.

- Seedlings are transplanted by hand (Figure 1.11), or by machines (Figure 1.13) to fields which have been flooded by rain or river water.

- Seedlings 25-30 days old, grown in a nursery are usually transplanted at 20 x 15 or 20 x 10 or 15 x 15 cm spacing in a well prepared main field and normally this will have a population of 335,000 to 500,000 hills/ha (33 to 50 hills/m2), whereby each hill contains 2-3 plants.

Figures 1.10 & 1.11: Traditional field preparation and transplanting

Figure 1.12: Germinating seeds for seedling transplanting

Figure 1.13: Rice seedling transplanter

1.10 Why flooding rice fields?

The traditional method for cultivatingrice is flooding the fields while, or after, setting the young seedlings. This simple method requires sound planning and servicing of the water damming and channeling, but reduces the growth of less robust weed and pest plants that have no submerged growth state, and deters any rodents and pests. Consistent water depth has been shown to improve the rice plants' ability to compete against weeds for nutrients and sunlight, reducing the need for herbicides. Rice crops are grown in 5–25 cm of water depending on growing conditions. While with rice growing and cultivation the flooding is not mandatory, all other methods of irrigation require higher effort in weed and pest control during growth periods and a different approach for fertilizing the soil.

1.11 Growth stages

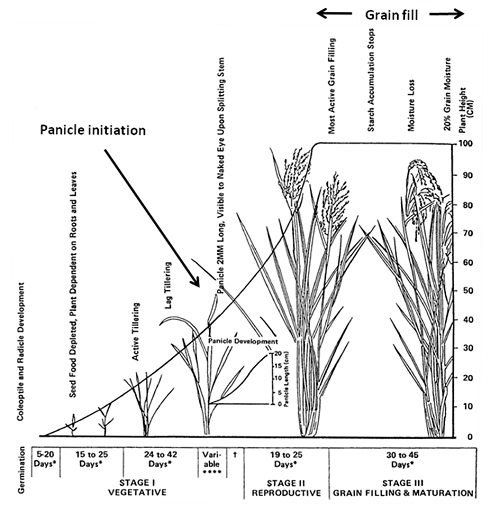

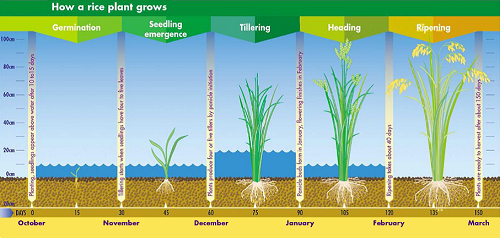

Rice plant grows a main stem and a number of tillers. Each rice plant will produce four or five tillers. Being a crop that tillers, the primary tillers (branches) grow from the lowermost nodes of the transplanted seedlings and this will further give rise to secondary and tertiary tillers. Every tiller grows a flowering head or panicle. The panicle produces the rice grains.

See Figures 1.14 and 1.14a.

Figures 1.14 and 1.14a: Development stages of the rice plant

1.12 Rice maturation and harvesting

Rice seedlings grow 4-5 months to maturity.

The plants grow rapidly, ultimately reaching a height of 90 cm (3 feet). By late summer, the grain begins to appear in long panicles on the top of the plant. By the end of summer, grain heads are mature and ready to be harvested. When still covered by the brown hull rice is known as paddy.

Depending on the size of the operation and the amount of mechanization, rice is either harvested by hand or machine. The different harvesting systems are as follows:

1.12.1 Manual harvesting

Methods of growing differ greatly in different localities, but in most Asian countries the traditional hand methods of cultivating and harvesting rice are still practiced. The fields are allowed to drain before cutting. Manual harvesting makes use of sharp knives or sickles, traditional threshing tools such as threshing racks, simple treadle threshers and animals for trampling.

1.12.2 Combine harvesting

Combine harvester combines all operations: cutting, handling, threshing and cleaning. In the United States and in many parts of Europe, rice cultivation has undergone the same mechanization at all stages of cultivation and harvesting as have other grain crops.

The soil dries out in time for harvest to commence. Farmers use large, conventional grain harvesters to mechanically harvest rice in autumn. Because quality is so important, these harvesters are designed to both gently and rapidly bring the grain in from the fields.

1.12.3 Quality of the harvested rice

Harvest management preserves rice quality and yield that contribute directly to profit. Timing field draining and harvest are keys to high head rice yields.

Other harvesting factors that affect head rice yield include grain moisture content, field rewetting of grain, severe threshing impacts and excessive foreign matter (trash) in rice.

Rice quality may be lower if rice is harvested either at high or low moisture contents. The ends of wet rice kernels grind off and become dust as they are processed. Rice may crack if it dries to below 15 percent moisture content. Rapid rewetting, once rice reaches 15 percent or less moisture content, is a key cause for lowered head rice yields. The recommended harvest range to avoid quality or yield reductions is 17 to 21 percent moisture.

Need more information about growing rice? You can always return to the rice fertilizer & rice crop guide table of contents